“All for ourselves and nothing for other people, seems, in every age of the world, to have been the vile maxim of the masters of mankind.” – Adam Smith in “The Wealth of Nations” Book III, Chapter IV

“Business leaders today face a choice: We can reform capitalism, or we can let capitalism be reformed for us, through political measures and the pressures of an angry public.” – Dominic Barton, Global Managing Director, McKinsey & Company

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Stagnating economies, helpless governments, depressed markets, diffident businesses, angry citizens. Is there a way out of this quagmire? What could point us in that direction? Without promising any categorical answers, this essay in three parts attempts to: (in Part I) understand how we got here, (in Part II) assess where we are today and (in Part III) look at what might unfold as the road ahead.

This essay does not aspire to be a formal, academically complete dissertation of the kind presented by an economic historian or a political scientist. It does not purport to be either an authoritative chronicle of our history or an all-encompassing narrative of our present condition or a forecast for the future of our species on this planet. Instead, it captures the observations and findings of a curious mind in its attempt to study the etiology of some major forces that have impacted our lives in the last few decades, leading to the severe systemic failures whose fault lines started to show about four years ago and the full dimensions of which are only now becoming clear.

A lot happened in the last 300 years, and this first part of the essay tries to put in perspective only those events and phenomena that have shaped the socioeconomic and political zeitgeist of our present times.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Part I: Understanding the Past

Around three centuries ago, the Age of Enlightenment and its attendant Revolutions – the Industrial Revolution, the American Revolution and the French Revolution – permanently reoriented the social, economic and political vectors of progress and redefined the trajectory of human civilization. The work of prominent inventors, economists, philosophers, social reformers and political revolutionaries such as James Watt, Adam Smith, Jeremy Bentham, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire, to name a few, triggered a series of changes through the 18th and 19th centuries. These changes – some incremental, some dramatic – fundamentally transformed continents on both sides of the Atlantic over those 2 centuries. Orthodox and rigid feudal hierarchies were broken down or relegated to irrelevance. A largely agrarian society ruled by dynastic monarchs gave way to industrialized economies in nation-states governed by elected representatives of the people. In addition to Land and Labor, a third dimension – Capital – became a vital cornerstone of economics. What came to be called the “Industrial Age”, framed in the ideological context of classical liberalism, brought along a new kind of prosperity and placed it within reach of common folk.

The world witnessed even more dramatic change as it entered the 20th century. The work of prominent scientists like Einstein, Heisenberg and Schrodinger changed the way the world looked at the universe. The atom was smashed and nuclear energy was harnessed – for constructive as well as destructive purposes. Leading manufacturers perfected the art and science of mass-production of goods in large volumes in a relatively short time using a smaller number of workers. Mass-produced and affordable automobiles changed how middle-class people got from place A to place B. Not only did Man learn to fly, but also managed to set foot on the moon and send several unmanned probes into the solar system and beyond. The discovery of penicillin opened a whole new chapter in modern medicine. Life expectancy nearly doubled. World population quadrupled in just a hundred years, despite mass destruction on an unprecedented scale (two World Wars, many other international conflicts and numerous genocides, that together accounted for the loss of close to a hundred million lives). Activist-reformers like Mohandas Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela demonstrated the power of non-violent civic protests to move (or remove) oppressive regimes. Colonial imperialists gave in to demands for independence and assertions of the right to self-determination from the outreaches of their dominions, and relinquished control to sovereign nation-states. The influence of social liberalism urged capitalist governments (more so in Europe than in America) to address issues such as unemployment, health care, education, civil rights and social justice. Thanks to rapid advances in telecommunications, broadcasting and data processing technologies, the “Information Age” was born, adding a fourth dimension – “Intellectual Capital” – to three-dimensional Industrial Age economics, to represent the new “Knowledge Economy”.

Plus ça change plus c’est la même chose

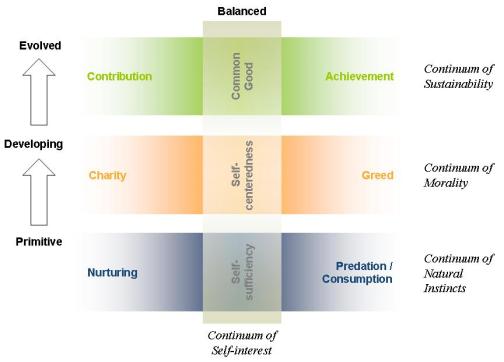

Unlike imperial feudalism (and its Indian manifestation, religious casteism), the secular polity of industrialized republics enabled citizens, including those of humble background (or “low” birth) to shape their own destiny. While the old order consigned people to their fate by an accident of birth and confined their lives to the boundaries of the specific cell of the societal matrix that they were born into, the new order accorded official sanction to the inalienable rights of all citizens to equally enjoy the same degrees of freedom, allowing for unencumbered upward mobility through socioeconomic strata (at least in theory) based on each individual’s ambitions, abilities and achievements.

Despite these dramatic changes, the core socioeconomic architecture withstood the tectonic shifts of these new Ages. While the quintessentially feudal arc of civilization (of the time) did bend – towards liberty, equality and fraternity – it did not break. A new combination of money and political power, accessible to common citizens of a republic, replaced the old combination of patrimony and inhered aristocracy that was reserved exclusively for those of noble birth and kept beyond the reach of commoners. Hierarchies based on nobility were brushed aside, only to be replaced by hierarchies based on economic and political control, built by capitalism and its doppelganger, communism. A late entrant on the world stage (born out of two other Revolutions in the 20th century: the October Revolution in Russia and the Cultural Revolution in China), communism made an early exeunt in one case and in the other, is currently undergoing its own unique drama of metamorphosis before a global audience. But even communist regimes that championed classless society needed some form of command-and-control architecture to organize their realms and maintain order.

Left or right, might continued to be right – the pyramidal shape of power structures hardly changed much. The harbingers of the new era of prosperity were exalted as the new lords and masters. In capitalist economies the nouveau riche emerged as the new upper class whose conspicuous consumption was designed to flaunt their newly amassed wealth to gain entry into elite social circles. Though slavery (in the United States) and casteism (in India) were abolished by law, old prejudices still remained. Centuries of social oppression, supposedly compensated by the patronage of whimsical aristocrats acting out of noblesse oblige, gave way to economic exploitation in the new capitalist model, ostensibly redeemed by the personal altruism of arriviste industrialists and (later) the institutionalized caritas of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programs. In the new totalitarian communist republics, individual and political freedoms were suppressed in the name of the “great leap forward” towards an egalitarian society.

And so dominance of one kind gave way to dominance of another kind. The barbarism of Ivan the Terrible and Genghis Khan resurfaced as the Industrial Age despotism of Stalin and Mao in the communist republics of the Soviet Union and China, matched equally by the fascism of Hitler and Mussolini in capitalist Germany and Italy. The tyranny of aristocratic feudalism was replaced by the authoritarianism of leaders of neo-feudal republics, on both sides of the infamous “Iron Curtain” that defined a bi-polar world. While this new avatar of feudalism manifested in the form of dirigistic oligarchies in communist countries, in the United States it resulted in crony capitalism and plutocracy in the form of the robber barons of the gilded age and the military-industrial complex in later years, for which an entity called the corporation served as the linchpin.

Portrait of the Corporation as a Psychopathic Person

The corporation became the most powerful non-state actor in the theater of the Industrial Age, exerting strong influence on politics and impacting all levels of policy-making and governance. In the documentary film The Corporation (released in 2003) Mark Achbar and Jennifer Abbott study the behavior of corporations, in much the same manner as psychologists analyze people, and conclude that corporations exhibit behavior that would be classified as psychopathic when observed in humans. Reproduced below are excerpts from the synopsis of the film.

In the mid-1800s the corporation emerged as a legal “person.” Imbued with a “personality” of pure self-interest, the next 100 years saw the corporation’s rise to dominance. The corporation created unprecedented wealth but at what cost? The remorseless rationale of “externalities” (as Milton Friedman explains, the unintended consequences of a transaction between two parties on a third) is responsible for countless cases of illness, death, poverty, pollution, exploitation and lies.

[…]

The operational principles of the corporation give it a highly anti-social “personality”: it is self-interested, inherently amoral, callous and deceitful; it breaches social and legal standards to get its way; it does not suffer from guilt, yet it can mimic the human qualities of empathy, caring and altruism.

A few years after this film was made, a study conducted by psychologists in the U.K. tested senior managers and chief executives from leading British businesses and compared the results to the same tests on patients at Broadmoor special hospital, where people convicted of serious crimes were held in custody. The study found that on certain indicators of psychopathic traits, the executives’ scores matched or exceeded those of patients who had been diagnosed with psychopathic personality disorders, consistent with the message of the film.

During the making of the documentary film, Canadian law professor and legal theorist Joel Bakan wrote the book “The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Power” in collaboration with Mark Achbar. The book traces the corporation’s rise to dominance and urges restoration of the corporation’s original purpose, to serve the public interest, calling for re-establishment of democratic control over the institution[1].

While the film won many awards and was generally acclaimed for being balanced in its approach of including a variety of different views, strident advocates of free market capitalism dismissed its scathing commentary as propaganda by left-leaning activists[2]. Ironically, the film was also criticized by Maoists for “depicting the communist party in an unfavourable light, while adopting an anarchist approach favoring direct democracy and worker’s councils without emphasizing the need for a centralized bureaucracy” (quoted from the Wikipedia page). Clearly, neither capitalists nor communists liked to be seen as psychopathic, though the former emphasized their moral superiority over the latter by pointing to the latter’s horrific crimes.

“If You Think I’m Bad You Should See The Other Guy”

On the eastern side of the Iron Curtain, communist totalitarianism gave a far more gruesome and macabre meaning to institutionalized psychopathic behavior (Stalin’s pogroms and Mao’s purges stand out even today as the most shocking instances of organized mass murder on a scale yet unprecedented in human history) making the evils of capitalistic institutions, in comparison, look about as diabolical as the antics of mischievous school children out on a picnic.

In its initial stages though, communism looked like it was the “right answer”. Lincoln Steffens, an American journalist and reformer visited the Soviet Union in March 1919 and on his return, uttered the famous words: “I have seen the future, and it works“. He went on to comment on the “confusing and difficult” process of a society in the process of revolutionary change, writing that “Soviet Russia was a revolutionary government with an evolutionary plan”, enduring “a temporary condition of evil, which is made tolerable by hope and a plan” (quoted from the Wikipedia page).

However, there was nothing temporary about the denial of personal and political freedom to common citizens of Soviet and Chinese republics. Economic conditions steadily deteriorated in various parts of the Soviet Union, while the government remained preoccupied with the arms race with America and its allies. Despite many protests, especially from the non-Russian minority communities, repression continued unabated till the late 1980s. In China the Tiananmen Square protests, demanding economic and political reforms, were brutally quelled by the State. Demands for autonomy and social and cultural freedom in Tibet continue even today, and though the movement enjoys international support, it has been effectively kept in check by the Chinese authorities.

Just as the Industrial Age saw the deconstruction of feudalism, the Information Age precipitated the dismantling of Soviet autocracy and compelled Chinese statists to rework their economic ideology. Two key weaknesses in the design of communism as the ideal socioeconomic model rendered it unsustainable: (i) the intrinsic inability of the model to foster innovation (a direct result of precluding free enterprise and competition) at a time when consumers in free market economies enjoyed abundance of choice in all categories of goods and services, and (ii) the intrinsic inability of the model to prevent abuse of individual freedoms and civic liberties by the autocratic regimes that it spawned (a direct result of concentrating power in the hands of the State) at a time when elsewhere in the world such freedoms were taken for granted, and free-thinking technocrats of the emerging Knowledge Economy, empowered by access to resources, tools and networks, openly communicated and exchanged ideas with one another.

The Golden Age of Capitalism: a Cornucopian Paradigm

According to many economic historians, the “Golden Age of Capitalism” and the rise of the consumerist society in the two decades or so following World War II were but a natural consequence of the Great Depression[3] from the decade preceding that war. This is consistent with the theory of business cycles, as envisaged by John Maynard Keynes, that anticipates fluctuations in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) caused by phase lags in production and consumption and other factors such as fiscal and monetary policies.

Despite the Great Depression, the 20th century was the most economically prolific period in history. According to a recent study 55% of all the goods and services produced since 1 AD were produced in the 20th century. Much of this was due to the strategically and pro-actively planned promotion of a consumerist culture in America in the aftermath of World War II, quite possibly taking a cue from a paper titled “Price Competition in 1955” published in the Journal of Retailing, Spring 1955 by economist and retail analyst Victor Lebow. Excerpted below are Lebow’s “best-known words” from that paper (source: Wikipedia):

Our enormously productive economy demands that we make consumption our way of life, that we convert the buying and use of goods into rituals, that we seek our spiritual satisfactions, our ego satisfactions, in consumption. The measure of social status, of social acceptance, of prestige, is now to be found in our consumptive patterns. The very meaning and significance of our lives today expressed in consumptive terms. The greater the pressures upon the individual to conform to safe and accepted social standards, the more does he tend to express his aspirations and his individuality in terms of what he wears, drives, eats- his home, his car, his pattern of food serving, his hobbies.

These commodities and services must be offered to the consumer with a special urgency. We require not only “forced draft” consumption, but “expensive” consumption as well. We need things consumed, burned up, worn out, replaced, and discarded at an ever increasing pace. We need to have people eat, drink, dress, ride, live, with ever more complicated and, therefore, constantly more expensive consumption. The home power tools and the whole “do-it-yourself” movement are excellent examples of “expensive” consumption.

It is not clear whether Lebow was actively advocating a consumerist culture or cynically apprehending its preponderance. It is also not clear whether the policy makers of the time took Lebow’s advice into account in envisioning an economic future for America. Notwithstanding these ambiguities, what seems clear now in hindsight is Lebow’s prescience of the design principles of post-World-War-II capitalism. Not only did this strategy work, it “rocked”. Leading historian and academic Niall Ferguson’s recent book lists consumption (and the consumerist lifestyle) as one of the 6 killer apps of prosperity that have made the “West” more successful than the “Rest”.

Consumerism: The Benchmark for Calibrating Progress

The resounding success of consumerist capitalism has entrenched in our minds – in the West as well as among the Rest – the baseline definition of progress. We have been so deeply conditioned to treat the cornucopian abundance of such booms as “normal”, that after every bust that invariably follows every boom, this “Golden Age of Capitalism” is what we seek to return to. When we find we just can’t, we reset our expectations to a “new normal” – one that advocates austerity measures but doesn’t change the culture that drives consumerist aspirations and lifestyle goals. This leaves us frustrated and angry.

What we don’t realize despite occasional reminders by insightful thinkers, is that consumerism as the path to socioeconomic utopia is an idea whose time has gone, as Tim Jackson, economics commissioner on the U.K. government’s Sustainable Development Commission, explains in his TED talk. If the entire population on planet Earth were to adopt the same consumerist lifestyle as citizens of the Western hemisphere, we would need more than one planet Earth to provide the natural resources needed to support that level of consumption. Physicist and blogger Tom Murphy points out that if one were to “do the math“, it would be obvious that growth has an expiration date. However, developing countries like India, even today, aspire to reach their own golden age of prosperity, unmindful of the pitfalls of Western-style consumerism, though studies[4] show that over-harvesting of natural resources to support growing consumerism could lead to disastrous consequences.

There are many insidious implications of stretching the consumerism formula too far, as the industrialized free market economies did over the second half of the 20th century. Competitive forces in a market economy put considerable pressure on pricing of goods and services, and corporations respond to these forces by developing a variety of strategies aimed at reducing costs at each step of the supply chain (sourcing/ procurement; production; distribution/ delivery). Many (but not all) of these cost-cutting strategies involve “externalization” of costs (as noted in the synopsis of the film “The Corporation” excerpted above). The cost incurred by the corporation (and therefore, the unit cost to the consumer) is indeed lower, but when seen from an overall ecosystem perspective, several cost components are merely taken out of the corporation’s accounting system and transferred on to externalities.

Some examples of the “unintended consequences” of these types of cost reduction strategies include: exploitation of migrant/ overseas workers (sweat shops, child labor, human trafficking and slavery); un-/ under-employment of local labor; neglect of employee health and safety standards; unfair land acquisition and/ or eviction of residents from sites targeted for new plants/ factories/ other corporate premises; depletion of natural resources that cannot be replenished; release of untreated harmful effluents into the ecosystem; careless disposal of waste (non-biodegradable, in many cases) that can be toxic; change in the habitat of local flora and fauna and reduction in biodiversity.

The Grammar of Plutarchy

Clearly, such indirect ramifications of fierce competition among corporations in the consumer supply chain adversely impact social harmony and the ecological balance. The cheaper-faster-better mantra usually turns out to be worse and more expensive in the long run, for corporations’ stakeholder ecosystems and host societies as a whole. However, the powers that be, who benefit from the status-quo, would not have it any other way. This model works for them and they are the ones who call the shots.

Plutarchy, a portmanteau word that conflates plutocracy (rule by the wealthy) and oligarchy (rule by a few), is probably the word that best describes the collusion between the State and the Corporation, based on the nexus between affluent business tycoons and politicians. Drawing on our perspective on the evolution of Industrial Age capitalism over the last 3 centuries as described above, and on the insights shared by observers and analysts highlighted above, we may conclude that capitalist plutarchy is founded on the following underpinning beliefs and imperatives:

| # | Beliefs | Imperatives |

| 1. | Consumerism is good. A consumerist culture promotes the good life by granting citizens the liberty to choose from an array of products and services for each category of needs. Competitive forces in free markets trigger innovation, increasing variety. The pursuit of happiness finds its rewards in consumption. | Create and sustain a culture of consumerism. Design economic policies, social norms and traditions, and cultural values that spur an ever increasing demand for consumer goods and services, and in doing so facilitate the growth of corporations that constitute the value chain of consumerism. |

| 2. | Free markets are good. The freer the market the better. A totally free global economy will develop market-based solutions to all socioeconomic problems anywhere in the world[5]. | Promote the advocacy of free market economics by funding and supporting economists, intellectuals, think-tanks and opinion makers aligned with this philosophy. |

| 3. | Cronyism at the top of the pyramid is but a natural and inevitable consequence of economic hierarchy. Cooperation among the wealthy and powerful ensures survival and mutual prosperity. The crony network should be robust enough to protects its members and their business interests by controlling policy making, regulation and governance processes, and exclusive enough to make those outside of it curry favors to gain admittance. | Cultivate influential politicians, bureaucrats and lobbyists, powerful regulators and enforcement officials, clever accountants and lawyers and upright judges with a formidable reputation. Include media moguls and executives of publishing houses aligned with free market/ consumerist ideology. Become the definition of success. Exemplify the “lifestyles of the rich and famous” and set it as the gold standard for people’s aspirations (in the U.S., that would be the “American dream”) |

| 4. | Governance and regulation are necessary evils. The smaller the regulatory footprint the more manageable it is to get your way around it, and the cheaper it is to finance its implementation and administration. Laws and policies must be seen to represent the best interests of the common people and must appear fair and just. However, there must be adequate provisions to support the interests of the crony network. Gaming the system, bending or breaking rules is OK if you can get away with it – this is the natural instinct of self-interest. | Minimize the scope and scale of government. Keep taxes as low as possible (small government requires less funding). Ensure that the regulatory framework contains adequate loopholes and escape hatches (known only within the circle of cronies) that can be exploited by cronies when necessary. Hire “fixers” who can resolve complex compliance issues, by working outside the system if needed. Leverage the crony network to ensure that corporate misconduct and administrative malfeasance by its members remains hidden, or even if exposed, goes unpunished. |

| 5. | Propaganda works. Mass media can help shape public opinion. Deny a truth vehemently and often enough, and it becomes an untruth. Assert a lie stridently and often enough (“Emperor’s new clothes”) and it becomes the truth. | Hire smart PR and advertising agencies. Leverage the crony network to control the media. Silence critics, contrarians and whistle-blowers and demonize them[6] as anti-national and enemies of capitalism/ true democracy. |

| 6. | Authoritarianism is the only real form of leadership. People in general respect and fear authority – they will genuflect before it and take orders from it, thanks to the discipline of obedience taught by religion. However, there could be the exceptional rebel. Social activism and protests are organized forms of anti-establishment rebellion and can be dangerous if not checked. Grassroots/ participatory democracy is synonymous with anarchy and should be avoided. | Always remain in control, on “top of the food chain”, at the apex of the power pyramid. Ensure that this power structure is never threatened. If it is, nip the bigger threats in the bud. Allow some room to smaller threats, to demonstrate tolerance for freedom of expression, and leverage that allowance to advertise democratic values. Always keep grassroots activism in check. Never let things get out of hand, and if they do, then respond by astroturfing or greenwashing or any other tactic money can buy. |

| 7. | There will be always be a divide between the rich and the poor. This is God’s will, and cannot be changed[7]. Where the gap is too wide, charity helps reduce the disparity. Charity is an obligatory duty to be performed by the rich towards the poor, and provides the rich with an opportunity for penance should they feel guilty about overindulgence in economic greed. Ergo, charities should never make money. Donations are also a useful tactic to keep the underprivileged dependent on the generosity of the privileged, and therefore preclude them from developing entrepreneurial skills. This helps in creating evidence that they are lazy and parasitic[8], and also reduces future competition. | Indulge generously in eleemosynary acts, for not only is charity the best solution to poverty, it is the best path to a venerable image of moral righteousness. Use charity to keep the status-quo. Maintain the gap between the “haves” and the “have-nots” by designing charity programs in a way that makes recipients dependent on donors while simultaneously making them feel indebted. Leverage that indebtedness when needed. If you must “teach people to fish” make sure to remain the thought leader or else risk creating better fishermen who may surpass you. Squeeze all the possible mileage out of charitable acts to earn goodwill and save on taxes. |

| 8. | This is as good as it gets. This model of civilization (i.e. consumerist free market capitalism in a democratic republic led by the righteous elite) has worked for several years and has proved to be the best path to prosperity. It may be imperfect but it is better than all other alternatives that can possibly exist. It has produced more prosperity and delivered more personal freedoms than any other system of organizing social and economic activities of a people. If this model doesn’t work for a certain set of individuals, it is because they are indolent and/or incapable of enterprise or industry. | Objections and criticisms pointing to minor imperfections in this model, when accompanied by suggestions for improvement, are valid and are to be welcomed in the name of openness and democracy. Other objections and criticisms, to the effect that this model is fundamentally flawed, can only come from lazy leftist losers, and are therefore invalid and need to be summarily dismissed. Neutralize them using the devices and machinations of crony authoritarianism. As per the principles of Manifest Destiny[9] this model must be replicated globally and it is the moral duty of the leadership of the free world to ensure that it is. |

.

None of this might come as a surprise to the average reader who has been “in the system” for some time and seen up close these beliefs and imperatives playing out in various aspects of our daily lives. This neo-feudal model of Plutarchy has become such an integral part of our cultural DNA that we seldom stop to think about its validity today or its ability to support future generations. And if we do, our response is likely to be a resigned shrug accompanied by: “It is how it is” and an impatient wave of hand dismissing the suggestion that there could be, and perhaps should be, alternative models that might help us build a better future for a larger number of people over a longer period of time.

However, towards the last few decades of the 20th century, as the golden age of capitalism started losing its luster, various groups of people – thinkers and doers alike – in various parts of the world rose to challenge the validity of this model despite its resounding success. According to them, the relentless pursuit of this consumerist model of utopia, by an exponentially increasing world population, could only lead to dystopia.

Sturm und Drang, Reprise

The many philosophical, artistic, cultural and social movements that took root in the wake of the devastation and misery wrought by the two World Wars – existentialism (Sartre, Camus et al.), surrealism (Dali, Magritte et al.), the theater of the absurd (Beckett, Ionesco et al.), film (Kubrick, Tarkovsky et al.), rock music (The Beatles, The Doors et al.), civil rights (Martin Luther King Jr., Nelson Mandela) – inspired and shaped the socio-cultural revolutions of the 1960s and 70s. In a throwback to the Romanticism that emerged in the late 18th/ early 19th century as a reaction to the Industrial Revolution, these two decades witnessed a widespread backlash from civil society (especially youth/ students), protesting the inhumanity of war (in particular, the use of nuclear weapons) and promoting world peace; protesting the indiscriminate exploitation of natural resources and promoting ecological balance; protesting racial and gender discrimination and promoting a more inclusive and egalitarian social outlook.

The hippie movement fostered a subculture that campaigned for love and peace and harmony with nature, and prescribed sexual freedom, experimentation with drugs and indulgence in Eastern mysticism as catalysts to self-exploration and self-actualization, unconstrained by the conventional morality of a materialistic technology-driven world steeped in social protocols and (according to them) a false sense of propriety. Authors, musicians and other artists of the “Beat Generation” encouraged a rejection of the status-quo established by the “masters of mankind” and unleashed the angst and frustration of repressed youth worldwide. James Michener’s novel “The Drifters” traces the story of six young characters as they navigate their lives, rejecting lifestyles dictated by an authoritarian establishment, in their honest search for meaning and purpose. As a work of fiction, this novel serves as an excellent documentation and reference point for the intellectual chaos of the youth of the time and their quest for a new reality that was more free and fair, and more environmentally and socially responsible.

When it became apparent that the counterculture spawned by hippies and beatniks (the “baby boomer” generation, in today’s parlance) was incapable of solving world problems (or in fact even sustaining itself as a revolutionary movement), many of these non-conformist “revolutionaries” gradually found their way back into the mainstream, to not only conform to it but in many cases further strengthen and propagate its principles. However, many others dug their heels in and took the fight deeper into the various spheres (environmental conservation, global development, social justice, feminism, etc.) that collectively constitute “green politics” and form its intellectual, ethical and cultural ethos.

The Green Movement and the Genesis of Sustainable Development

In the late 60s and early 70s several initiatives aimed at focusing global attention on ecological issues were launched, of which Greenpeace and the Green Party are prime examples. The foundation of green politics rests on the “Four Pillars” defined by the Green Party: Ecological Wisdom, Social Justice, Grassroots Democracy and Nonviolence. These four pillars “define a Green Party as a political movement that interrelates its philosophy from four different social movements, the peace movement, the civil rights movement, the environmental movement, and the labour movement.” (quoted from Wikipedia).

Since 1970, Earth Day has been observed every year as a day on which events are held worldwide to increase awareness and appreciation of the Earth’s natural environment. “The name and concept of Earth Day was allegedly pioneered by John McConnell in 1969 at a UNESCO Conference in San Francisco. The first Proclamation of Earth Day was by San Francisco, the City of Saint Francis, patron saint of ecology. Earth Day was first observed in San Francisco and other cities on March 21, 1970, the first day of spring in the northern hemisphere.” (quoted from Wikipedia).

In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) commenced operations in late 1970. Many other countries set up their own EPAs, charged with responsibility of defining national standards and regulations aimed at protecting the natural environment and also conducting environmental research and disseminating information to create awareness.

Over a decade or so, the scope of the Green Movement expanded into other initiatives such as Sustainable Development. The United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development released the Brundtlandt Report in 1987, which defined Sustainable Development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” This central idea continues to be at the core of the thinking that has emerged over the years and today offers itself as the North Star to the ideation around evolving a better world. This theme runs through the next two parts of this essay, as we go on to discuss our present circumstances and envision strategies for the future.

________________________________________

Endnotes

1. Quoted from the web-page about the book:

Beginning with its origins in the sixteenth century, Bakan traces the corporation’s rise to dominance. In what Simon and Schuster describes as “the most revolutionary assessment of the corporation since Peter Drucker’s early works”, The Corporation makes the following claims:

- Corporations are required by law to elevate their own interests above those of others, making them prone to prey upon and exploit others without regard for legal rules or moral limits.

- Corporate social responsibility, though sometimes yielding positive results, most often serves to mask the corporation’s true character, not to change it.

- The corporation’s unbridled self interest victimizes individuals, the environment, and even shareholders, and can cause corporations to self-destruct, as recent Wall Street scandals reveal.

- Despite its flawed character, governments have freed the corporation from legal constraints through deregulation, and granted it ever greater power over society through privatization.

2. It is worth noting here that, thanks to the draconian power of McCarthyist witch-hunts of the 1950s which managed to expunge all forms of socialist/ collectivist ideologies from American intelligentsia, people enjoyed freedom of thought only as long as they did not advocate communism. Even today, articles pondering over the wisdom in Karl Marx’s ideology are peppered with apologia in an attempt to clarify and reiterate their pro-capitalism position. A recent post in the blogs sections of Harvard Business Review titled “Was Marx Right?” is an instance in point.

3. In a recent New York Times article comparing the current economic crisis with the Great Depression, David Leonhardt writes:

Economists often distinguish between cyclical trends and secular trends — which is to say, between short-term fluctuations and long-term changes in the basic structure of the economy. No decade points to the difference quite like the 1930s: cyclically, the worst decade of the 20th century, and yet, secularly, one of the best.

[…]

Partly because the Depression was eliminating inefficiencies but mostly because of the emergence of new technologies, the economy was adding muscle and shedding fat. Those changes, combined with the vast industrialization for World War II, made possible the postwar boom.

4. “If the levels of consumption that … the most affluent people enjoy today were replicated across even half of the roughly 9 billion people projected to be on the planet in 2050, the impact on our water supply, air quality, forests, climate, biological diversity, and human health would be severe.” (Excerpted from “The State of Consumption Today“; source: “State of the World 2004” published by the Worldwatch Institute.)

5. This belief is based on the assumption that materialistic ambition of individual entrepreneurs invariably results in benefits to society, though the motive is purely based on personal gain. Adam Smith used the metaphor of an “Invisible Hand” that guides free enterprise in its intention to maximize profits, to produce outcomes aligned with the common good. A logical corollary to this belief is, in the words of John Maynard Keynes, “the belief that the most wickedest of men will do the most wickedest of things for the greatest good of everyone.”

6. Economist Paul Krugman in the New York Times op-ed “Panic of the Plutocrats“: “Anyone who points out the obvious, no matter how calmly and moderately, must be demonized and driven from the stage. In fact, the more reasonable and moderate a critic sounds, the more urgently he or she must be demonized …”

7. Paraphrased from the opening line in John Winthrop’s sermon “A Model of Christian Charity“, in which he called for the establishment of a virtuous community – “City upon a Hill” – that would be a shining example to the rest of the world. It may be noted that many American politicians throughout the country’s history, including present times, have made references to Winthrop’s metaphor in their speeches, suggesting that his vision remains a keystone of America’s view of itself and its relationship with the rest of the world, even today.

8. This goes against the Protestant work ethic that forms the spirit of capitalism and therefore constitutes a strong moral judgment, liable for punishment in the form of poverty.

9. See Wikipedia page on Manifest Destiny. Relevant excerpt:

Historian William E. Weeks has noted that three key themes were usually touched upon by advocates of Manifest Destiny:

- the virtue of the American people and their institutions;

- the mission to spread these institutions, thereby redeeming and remaking the world in the image of the U.S.; and

- the destiny under God to do this work.

.